Keep Black Monday market crash in mind, says former Treasury Secretary

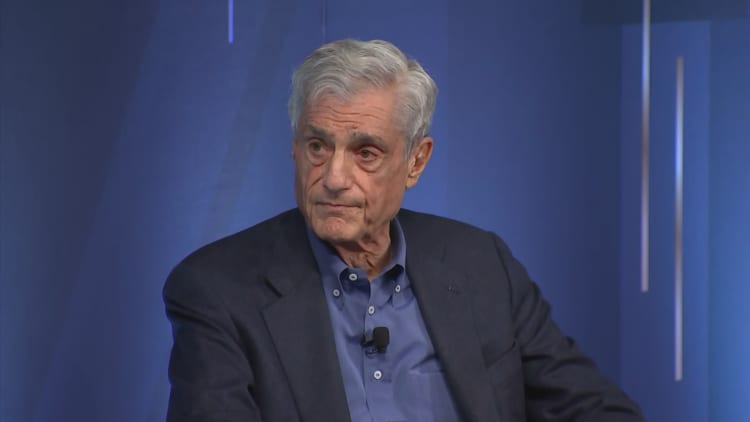

The market has been consumed in recent weeks by concerns about tech stock valuations and an AI bubble in the making. But for former U.S. Treasury Secretary and former Goldman Sachs co-chairman Robert Rubin, market complacency runs much deeper than any current debate over whether record market highs can be sustained by a handful of growth stocks. In his view, debate over the current AI boom and whether it will resemble the financial crash or dotcom bubble misses the point. October 1987, and what is known as “Black Monday,” is the historical comparison he is asking the market to focus on.

Rubin has been outspoken about the risks the U.S. economy is running related to the increase in government debt, and he expanded on those concerns at the CNBC CFO Council Summit in Washington, D.C., on Wednesday.

Recent estimates from the Congressional Budget Office put the debt held by the public at 99.8% of gross domestic product for fiscal year 2025. That is twice the historical average of 51% over the past 50 years. But Rubin noted that long-term average masks a trend that has been worsening more recently. In 2000, the same ratio was at 30%.

The CBO projects that it will rise by another 20 percentage points over the next decade, but Rubin sees that forecast as optimistic. “More realistic estimates,” he says, “are substantially higher.”

He cited work from the Budget Lab at Yale that forecasts a debt to GDP ratio closer to 130-140%, not counting tariffs.

The effects of the rising debt are just barely beginning to be felt. Constrained spending on public investments and national security, as well as some impact on interest rates, are likely already related to the debt load, he said. And to a very limited extent, Rubin added, business confidence may have also taken a hit.

But the “ultimate serious consequences,” which Rubin said he believes are “highly likely to be out there,” lead him back to October 1987.

“When I talk to people in the markets, I say there is one date you ought to keep in mind: Oct. 19, 1987,” Rubin told CNBC senior finance and banking reporter Leslie Picker at the Summit.

He said that for years before the October 1987 crash, conditions were considered to be “highly in excess and nothing happened in the markets.”

The result: “People stopped listening,” Rubin said.

And then the Dow Jones Industrial Average was down over 22% in one day on Oct. 19, 1987.

Scene at the Pacific Stock Exchange on Oct. 19, 1987, the day the Dow lost 509 points, at that time a decline equal to over 22% of the index value.

San Francisco Chronicle/hearst Newspapers | Hearst Newspapers | Getty Images

The most current outspoken market voice on the AI bubble is short seller Michael Burry, who recently closed his hedge fund but has started a newsletter to expound on his views and warned on Wednesday that within two years the AI stock bubble could unwind.

On that infamous October day, Rubin noted that no specific action triggered the crash other than “just markets being out of sync with reality.”

In the current economic environment, Rubin said he thinks there is a “quite high probability” that eventually actions will have to be taken that lead to adverse consequences, though it is the debt and not the AI valuations that he is thinking about mostly, such as the government attempting to “inflate its way out” of the problem — monetizing the debt to finance the purchase of new bonds. “But the timing is impossible to predict,” Rubin said. “And it is possible we can just keep doing things that are unsound, but that seems to me a very unsound bet to make,” he added.

Rubin said the AI issue itself is complicated, and especially for a company like OpenAI without the existing revenue and profit model of the public tech giants like Alphabet, the vast investments being made now in data centers “certainly poses some identifiable risks.”

“I don’t know what odds I would put on it having some really difficult ending, but it is really complex and we really need to come to grips with this,” Rubin said.

He does see one parallel between AI and the larger financial issues for the U.S. in that the political system is not dealing with the implications of what is likely to come. Estimates that AI job displacement could reach 50% of white-collar professions do not need to be precisely right or wrong, he said, to make him believe the risk of “replacement of human effort by AI is very substantial and we should be dealing with it, but we’re not.”

Rubin said when he was running Goldman Sachs he always told staff that they need to be “actively involved and fully engaged” and right now he has a cautious bias because there are a lot of risks, from the debt to geopolitics, and “there are lots of ways it can go wrong and I don’t think the political system is dealing with it very well,” he added.

His estimates with the Budget Lab at Yale suggest that to get the current deficit to GDP ratio, roughly 7%, down by 2.5%, requires a combination of new taxes and less spending — to lower that ratio to 4.5%, it is reasonable to see one-half of one percent cut from spending and 2% added from tax revenue. Then, Rubin says, it would be possible to stabilize the debt to GDP ratio at 100%, basically where it is today. “And we would be at a far better place going forward for the economy.”

While the Trump administration has focused on the growth prospects for the economy as the linchpin of its plans, Rubin said to grow our way out of this debt and deficit issue would require growth rates “astronomically greater than anything that is realistic.”

“Maybe it will never happen,” he said. “Maybe we just keep going along.”

But Rubin said he is more disposed to a conservative bias, based on trying to be disciplined about risk and reward, and that leads him to the conclusion that all the risks will materialize in a more rather than less serious manner. That ultimate risk, he says, “already is probably pretty high, but who knows? It could be tomorrow or into the future. I don’t think there is any way to make that judgement.”

For what Rubin sees as too complacent a market, there is finally nothing more to say then it will all matter, he says, “when it does.”

<